| Musical | Historical Epic | Lavish Setting | British | Social Injustice | |

| 1958: Gigi | X | X | |||

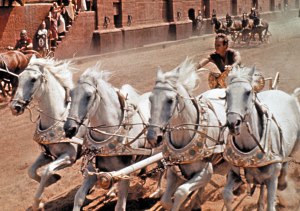

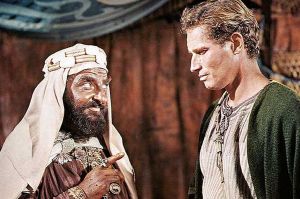

| 1959: Ben-Hur | X | X | |||

| 1960: The Apartment | |||||

| 1961: West Side Story | X | ||||

| 1962: Lawrence of Arabia | X | X | X | ||

| 1963: Tom Jones | X | X | |||

| 1964: My Fair Lady | X | X | X | ||

| 1965: The Sound of Music | X | X | X-ish | ||

| 1966: A Man For All Seasons | X | X | X | ||

| 1967: In the Heat of the Night | X |

This poster for Lawrence of Arabia really tells you all you need to know: Handsome man in white, lots of desert.

The Oscars fourth decade (1958-1967) is the start of the “traditional” Best Picture with the sorts of lavish costume dramas, period pieces and BRITISH-ness from the ten winners that dominate what we think of when we think of a “Best Picture type” today. It’s very notable that in a decade revered for its social consciousness and upheaval, only 3 of the 10 best pictures take place in the contemporary time period. It’s like the Academy – and perhaps moviegoers as a whole—looked to the escapism of movies for comfort from trying times.

None of this nonesense

Unique to this time period is the Academy’s absolute adoration of big musical spectacles. Before 1958, only two musicals ever won Best Picture. In this ten year stretch, 4 out of the 10 winners were musicals. In the next 50 years, we’ll only see two more musicals win. Oddly, aside from the success of the winners, the 60s are viewed as the decline of the Hollywood Musicals and you can probably count the successful musicals released between 1970 and 2000 on your fingers. Does this mean the Academy was behind the times? Regressing into the past to avoid the harsher realities of the present – both in terms of what was going on in the world and the struggles and changes within the filmmaking business? Or were they caught up in the zeitgeist and awarded the statue to the “right” winner – West Side Story, My Fair Lady and The Sound of Music are all much-remembered and well-loved to both audiences of their time and today’s fans.

Lots of jazz hands

The other major trend, carried over from the last decade, was the prominence of historical epics and the triumph of a movie’s “big-ness” that was used to compete with television. Ben-Hur and Lawrence of Arabia are two the most visually stunning and exciting Best Pictures ever. Even the non-epics like Tom Jones and A Man for All Seasons use their big budgets and location settings of movies to employ elaborate sets and costumes unlikely to be seen or appreciated on television at that time, perhaps another reason that period pieces fare so well among Best Pictures in this period.

One cannot deny the British influence over this time period (as with a lot of things in American culture – it was the British invasion, after all). From 1962-1966, four of the five Best Pictures are set in England and The Sound of Music, despite being in Austria, has a predominantly British cast and feel.

All hail the Union Jack!

Was the Academy out of touch? It’s well worth noting that the majority of the Best Pictures in this time frame were among the top ten financial grossers for their respective years of their release. The Sound of Music was the highest grossing movie of all time for a long period following its release. So it’s not as if the critical and commercial aspects of the Academy were as misaligned as they were today, when we have some of the lowest grossing Best Pictures ever. Even today, many of the winners are very highly thought of by some if not all – West Side Story, Lawrence of Arabia, and The Sound of Music, in particular. Hindsight has left many critics to question some of the Oscar choices – notably choosing In the Heat of the Night over Bonnie and Clyde and The Apartment over Psycho – but both those winners are very strong, in my opinion (There really is no defending Tom Jones, however), and it was impossible to know, for example, that Psycho would create a whole new genre of film.

Filmmaking was about to undergo a significant upheaval in the 70s and that is reflected in the Best Picture winners of that time period. For the Oscars in the late 50s and 60s, the Best Picture was about celebrating epics and style over social issues and “small” pictures.