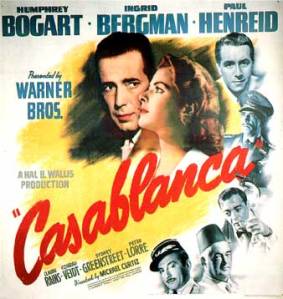

The 1950s’s Oscars – and 1950s pop culture in general – gets a pretty bad rap as white-washed, conformist and undaring. A lot of Oscar history books tend to throw out phrases like “Worst Collection of Best Picture nominees ever” (for 1956 from The Academy Awards Handbook) or “Least Deserving Best Picture Winner of All Time (For The Greatest Show on Earth from multiple sources including Alternate Oscars and The Official Razzie Movie Guide). However, I enjoyed this 10-pack of films much more than the previous decade of Oscar winners (even if none could match Casablanca). I felt that the movies began to “speed up,” by which I mean directors added more cuts and edits to make the movie feel faster as opposed to the relatively static filming styles of earlier times). Movies started to have a more modern look and feel as the science behind movie making advanced in this time period.

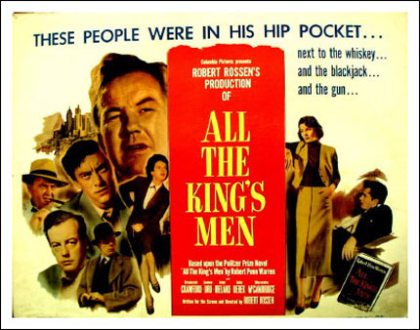

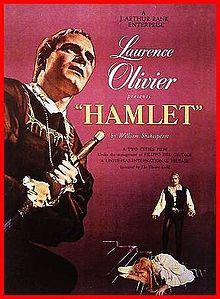

The third decade of Oscars also had a much more eclectic “something for everyone” nature to their themes and styles than what came in the previous decade. Most Best pictures from 1938-1947 were divided into the dual themes of either World War II or social ills and most (except for the extravagant Gone With the Wind) were middle-to-low-budget affairs, due to World War II cutbacks and the nature of the stories (a movie about alcoholism, for example, doesn’t need elaborate sets of shots of epic grandeur). From 1948-1957, the themes, styles and budgets of the Best Picture winners are all over the place. We start with a sparse recreation of a classic stage play, then move back to social ills with All the King’s Men, but on a larger scope than your Lost Weekends and Gentleman’s Agreements. Then we hit some lavish, big-budget, all color extravaganzas before heading to the smaller personal stories of On the Waterfront and Marty before going bigger than ever before in shooting style and budget with Around the World in 80 Days and the Bridge on the River Kwai.

| Corrupt Authority

/Society |

Small Scale | Epic/Big

Budg |

World War II | Social Ills | Sex | Modern Times | Gross | |

| 1948: Hamlet | X | X | X | $3.25M

(17) |

||||

| 1949: All the Kings Men | X | X | X | X | $3.5M

(10) |

|||

| 1950: All About Eve | X | X | $3.6M

(7) |

|||||

| 1951: An American in Paris | X | X | $4.5M

(6) |

|||||

| 1952: The Greatest Show on Earth | X | X | $14M

(1) |

|||||

| 1953: From Here to Eternity | X | X | X | X | X | X | $12.5M

(2) |

|

| 1954: On the Waterfront | X | X | X | X | $4.5M

(14) |

|||

| 1955: Marty | X | X | $2M | |||||

| 1956: Around the World in 80 Days | X | $23M

(2) |

||||||

| 1957: The Bridge on the River Kwai | X | X | X | X | $17.1M

(1) |

A few interesting common themes do emerge. In almost every one of these movies – even the seemingly incongruous Hamlet – there is a corrupt society or authority figure. Whereas the World War II era of movies showed a decided trust in leadership, the McCarthy Red Scare and perhaps other factors clearly altered the public’s faith in those who were supposed to guide them.

Did the public’s fear of Communism lead to so many Best Pictures about corrupt or broken authority and leadership?

Movies also began to look back on World War II with a more introspective, less rah-rah perspective then presented during the actual time of the War. Both Best Pictures dealing with World War II in this decade have bullying, corrupt and foolish leadership (Interestingly, From Here to Eternity was released at the tail end of the Korean War, a war considerably less popular and triumphant than World War II). Did the passage of time allow those who lived through the war to reconsider it, as appeared to happen in the 1920s and30s with movies dealing with World War I? Did the greater ambiguities and indecisive outcome of the Korean War change the public’s overall perception of war?

Another interesting note is the overall alignment between commercial and Oscar success. Between 1948 and 1957, 7 out of the 10 winners were in the top ten for their respective year’s box office and two were the number one movie for the year. Compare that to the past decade’s winners, when no Best Picture winners made their year’s top ten .There is a not altogether unfair assumption that today’s Oscar’s are out of touch with popular appeal, but that certainly did not appear to be the case in the late 40’s and 50s.

Here’s how the collective themes of the third decade stack up to the last ten Best Picture winners.

| Corrupt Authority

/Society |

Small Scale | Epic/

Big Budg |

World War II | Social Ills | Sex | Modern Times | Gross | |

| 2004: Million Dollar Baby | X | X | $216M | |||||

| 2005: Crash | X | X | X | X | $98M | |||

| 2006: The Departed | X? | X | $90M | |||||

| 2007: No Country for Old Men | X | $171M | ||||||

| 2008: Slumdog Millionaire | X? | X | $378M | |||||

| 2009: The Hurt Locker | X | X | $49M | |||||

| 2010: The King’s Speech | $414M | |||||||

| 2011: The Artist | X | $133M | ||||||

| 2012: Argo | $232M | |||||||

| 2013: 12 Years a Slave | X | $187M |

Period pieces are generally considered good Oscar bait and while this is true for technical categories like Art Direction (aka sets) and Costumes, this assumption clearly holds no water the 1940s-50 Best Picture winners or in today’s winners. In fact, even though the last four Best Picture winners could be considered period pieces under a rather broad definition (a movie set 30 or more years in the past where the look, dress and actions of the characters purposefully reflect the given time period), none of those movies really represent the haughty Merchant Ivory type fair that people really think of when describing a period piece (Calling Argo a period piece for example seems strange but it technically fits the definition).

Strangely, despite our increased distrust of big government, few Best Pictures of the last yen years represent a broken society or authority. (12 Years a Slave and Crash being the obvious exceptions. Slumdog Millionaire is a strange case in that the broken society is what ultimately provides the hero the keys to success. ) In fact, Kings Speech and Argo present government leaders and agencies working hard for the common good.

Another interesting note: While we typically think of the 60s as the advent of the sexual revolution and increasing depictions of sexuality on the screen, a surprising number of the 1950s Best Pictures deal with sexuality in some form, usually with at least a hint of scandal to them (dating back to Hamlet, where Olivier intentionally gave emphasis to Hamlet’s obsession with his mother’s sex life). Several of the Best Picture winners had affairs between unmarried people or extramarital affairs. Meanwhile, one could argue the last decade’s collection of Best Picture winners are among the least sexy – and sexless – collection of movies ever assembled.