“This is the tragedy of a man who could not make up his mind.” – Narrator, dumbing down the plot of Hamlet

“This is the tragedy of a man who could not make up his mind.” – Narrator, dumbing down the plot of Hamlet

Hamlet, 1948’s Best Picture, is an unusual case among Oscar winners. Although many Best Pictures are adaptions of plays or books, Hamlet is the only one that is an adaptation of a classic renowned piece of literature you are most likely required to read in high school (there’s never been a Dickens adaption that won Best Picture, for example) (I suppose All Quiet on the Western Front now falls into the required high school reading list, but it was a relatively new book when it was made into a movie). Also because it’s Shakespeare, Hamlet is one of the most “play-ish” movies to ever win Best Picture although director Laurence Olivier employs many of the popular noir film techniques of the day to spruce things up.

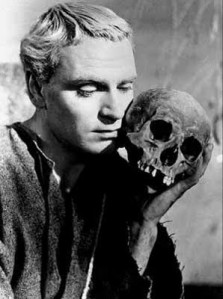

Since I assume everyone’s read Hamlet, I will give only a brief synopsis of the plot. Hamlet (Olivier), the prince of Denmark is depressed following his father’s death and the subsequent remarriage of his mother, Gertrude (Eileen Herlie) to his father’s brother, Claudius (Basil Sydney). Hamlet’s father’s ghost reveals to his son that Claudius, in fact, murdered the king and charges Hamlet with getting revenge. Hamlet, in a quandary about the situation, opts to feign madness in order to ferret out the truth, leaving a trail of havoc and death in his wake, mostly focused on his on-and-off again girlfriend Ophelia (Jean Simmons) and her father, Polonius (Felix Aylmer), the king’s pompous advisor.

So anyway, if you can remember Hamlet from high school or college English, you probably know what you are getting into here. Of note to English majors, is Olivier’s decision to cut three major characters – Rosencrantz, Guildenstern and Fortenbras – from the story as part of an overall slimming down of the story. The actual play runs four hours (!) (Kenneth Branaugh made a full version of it in the 1990s) and this movie clocks in at a trim(ish) 2.5. As noted, Olivier is also greatly influenced by the popular noir style of the time, with lots of shadows and low angles.

Olivier transforms many of the soliloquies from spoken words into overdubbed thoughts, with mixed results. Sometimes this effect is unintentionally laughable, especially when the actor is trying too hard to react to what they are thinking.

Olivier also focuses a lot on the relationship between Gertrude and Hamlet. While the exact nature of their relationship is one that has captivated lit majors for centuries, Olivier definitely has an opinion on it, including highlighting sequences where Hamlet is obsessed with Gertrude and Claudius getting it on and even having the mother and son give VERY tender kisses at a couple different times in the movie.

A cool shot with Claudius in the foreground and Hamlet in the back, as if haunting the King’s thoughts

Olivier’s Hamlet is considered a pinnacle of acting achievement, but the truth is it has not aged well. I found much of Olivier’s performance to be pretty hammy and very emotive. Today’s audiences are more attuned to a natural performer like Daniel Day Lewis, I think. I actually thought Simmon’s Ophelia gave a better performance as the batty Ophelia. Also, for whatever, reason, Olivier delivers the very famous “To Be or Not To Be” speech in a half repose, so that he looks utterly bored while reciting the single most famous speech in the history of English literature.

This is a fine production of Hamlet, but it’s not exceptionally notable or blows away other Hamlets. As noted, I liked the direction and sets a lot – the big empty castles are marvelous, the tracking shots that follow the characters up different flights of stairs or show different characters doing different things simultaneously are cool. But I think the reason there’s never been another Shakespeare movie to win Best Picture or very few adaptions of English Lit’s classical cannon have won is that these classical stories are so ingrained in our conscious they don’t have any surprises to offer us. They give us what we expect. Hamlet is a good production of Hamlet but it’s not going to blow you away.

Trivia: Laurence Olivier is one of only two directors to direct himself to the Best Actor award (the other was Roberto Benigni for Life is Beautiful in 1998).

Other notable movies in 1948: Johnny Belinda*, The Red Shoes*#, The Snake Pit*, The Treasure of the Sierra Madre*, Red River, Easter Parade, Key Largo

* Best Picture Nominee

#Top Grossing movie of the year