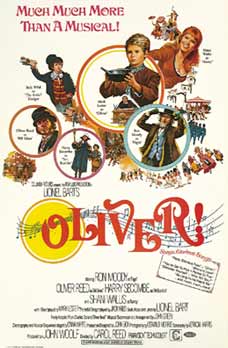

Even the poster is a bleak departure from what past movie posters had been.

“I ain’t a for real cowboy. But I am one helluva stud!” – Joe Buck (John Voight), selling his brand, Midnight Cowboy

You would be hard pressed to find two more different films than 1968 Best Picture winner Oliver! and the 1969 winner Midnight Cowboy. In fact, you’d be hard pressed to find two more different films than Midnight Cowboy and any of the 41 Best Picture winners that came before it. Midnight Cowboy is the ultimate line of demarcation between the glitz and glamour and happy endings of “classic” Hollywood and the gritty, arty and shocking New Hollywood that followed. Purposefully made cheap, with an emphasis on human degradation that the social problem movies of the 40s and 50s would never stoop so low to touch, Midnight Cowboy is painful and shocking but also deeply moving thanks to the wonderful performances by Jon Voight and Dustin Hoffman.

Voight is Joe Buck, a dim-bulb dish washer in a dead-end Texas town. Buck moves to New York with practically nothing except a career plan to become a gigolo (or “hustler” as he calls it) to all the rich, lonely women he’s heard about. Due to the plan’s numerous and obvious flaws, Buck is soon homeless and starving on the street. After getting conned by the slimy and crippled Enrico “Ratso” Rizzo, Buck is taken under Ratso’s wing. The pair live in a condemned tenant building without heat, running cons to occasionally eat and earning money by Joe turning tricks for a gay clientele. A chance encounter at a weird, Warhol-esque party leads Joe to a big score and the chance to finally become a big-time hustler. But Rizzo, who has been dogged by a nagging cough throughout the movie, is deathly ill and begs Joe to help him get to Miami.

Ratso Rico (Dustin Hoffman) helps clean up Joe Buck (John Voight), just one example of the characters’ real affection for each other.

Midnight Cowboy is a bleak movie. It’s not even really a “social ill” movie like Lost Weekend or The Best Years of Our Lives where a specific issue could be identified as the cause of the protagonist(s)’ distress and a solution offered. Instead, everything is wrong. Society is uncaring. Our two heroes have done nothing right and live with dirty dreams and constant screw ups. But through the bleakness, and maybe because of it, there’s some very affecting moments. The bond Joe and Ratso develop through the course of the movie is among the most touching relationships in cinema. They snipe and belittle each other, but underneath we see their real concern and affection. For example, Ratso tells Joe that the latter literally smells terrible and will never make it as a hustler because of this, but in the next scene we see Ratso help Joe con his way into cleaning his clothes.

The famous final bus scene in Midnight Cowboy will break your heart ten times over

The performances of both Voight and Rizzo are outstanding. Rizzo is essentially a nasty, unlikable guy, but Dustin Hoffman makes him so sad that we finally pity him. The scenes where the proud Rizzo finally has to beg Joe for help to get to Florida (he is deathly afraid of being sent to a pauper’s hospital) and the real terror he shows are painful to watch. Ratso’s dreams of being a big shot chef and lady killer in Miami with Joe by his side will rip into your heart. Voight brings an aw-shucks naivety to Joe, who is a likeable guy because he’s so nice, even if he is incredibly stupid.

Whereas many contemporary Best Pictures were big and straightforward, this movie is neither. There are lots of purposeful ambiguities to the story that weren’t found in traditional Best Pictures: Joe comes from a very traumatic past, where he was abandoned by his mother and possibly raped but these details are revealed only in dreams, giving the audience little concrete confirmation about what happened to him and what he’s running from. I like how the movie weaves the characters dreams and fantasies into their realities, moving without any kind of transition, a different kind of cinematic storytelling than had been seen before.

Midnight Cowboy is famously the only X rated movie to ever win Best Picture, but that piece of trivia comes with a few caveats. First, the X rating was originally supposed to be used for upscale pictures only adults could see but got co-opted after the fact by the porn industry and took on a whole different meaning later, after Midnight Cowboy won Best Picture. Second, the movie was re-rated as an R just two years later without any edits or cuts. It still earns a “Hard R” designation, make no mistake.

Other Awards: Best Director (John Scheslinger); Best Adapted Screenplay

Box Office: $44.8 Million (2nd for the year)

Other Notable Films of 1969: Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid*; Easy Rider; Z*; The Wild Bunch; True Grit; On Her Majesty’s Secret Service; Hello Dolly!*; Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice; The Shoot Horses, Don’t They?; Paint Your Wagon; Alice’s Restaurant; Once Upon a Time in the West; Anne of the Thousand Days*

*Best Picture Nominee