The original poster for A Man For All Seasons, another of the great Oscar posters that is significantly more exciting than the movie it is advertising.

“You’re a constant regret to me, Thomas. If you could just see facts flat-on, without that horrible moral squint… With a little common sense you could have made a statesman.” – Cardinal Wolsey (Orson Wells) to Thomas More (Paul Scofeld), A Man for All Seasons

Is A Man For All Season the Oscariest movie of all time?

Consider its traits: Period piece. True Story. British. Moralizing. Tragic ending. I don’t think in 1966 it exactly fit the ideal of a Best Picture – look at all the musicals that had just preceded it, not to mention Oscar’s rare dip into action films like Lawrence of Arabia (albeit a British true story action film) – but none of the 1960s movies would feel as at home in a Best Picture race today than A Man for All Seasons, a movie possibly well ahead of its time in its total squareness. This picture, while not bad or anything outside of being a trifle dull, is certainly one of the more fuddy-duddy pieces to take home the trophy from this period, similar to recent winners that have led to Oscar’s lambasting as out-of-touch (well, that and the race thing).

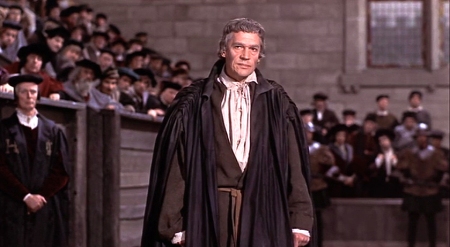

A ragged Paul Scofeld is tortured for his beliefs, but wins an Oscar and keeps his smug sense of superiority, in A Man For All Seasons

A Man For All Seasons is the true story of Saint Thomas More, a man who gave his life to keep his conscious clean (sorry for the spoiler for the true story of a man who lived 400 years ago). When the movie opens, More (Paul Scofield) is the rare honest judge in England’s corrupt political system. More could be a bigger player, but he refuses to compromise his conscious and take bribes or give favors to the rich and powerful. Meanwhile, King Henry VIII, lacking a male heir, wishes to divorce his wife and marry a new one. The Pope refuses to annul the marriage, even though Henry has found a clever legal loophole to have it tossed aside (his wife was married to his brother previously). Henry dissolves the Catholic Church in England and starts the Church of England, with himself as head. More, who has become a Cardinal, hopes to escape Henry’s wrath by simply not saying anything about the marriage or Henry’s power play. Because of More’s status, Henry won’t let the matter rest, using a series of sycophants and suck-ups to coerce either an acceptance of the marriage or to get More to speak out against it (which would be viewed as treasonous and leave More open to a death sentence). More is imprisoned and ultimately betrayed by a former subject whose career he refused to help advance (a very young John Hurt). More, sentenced to death, finally denounces Henry’s actions in a stirring speech that seems too dramatic to be real, but apparently did happen (according to the attached documentary on the DVD).

I would be remiss in not mentioning Orson Welles as the corrupt Cardinal Wolsey who sold his soul for riches and meatloaf.,

Much like Sound of Music rested on Julie Andrews’s shoulders, Scofield carries A Man for All Seasons. I like that the movie isn’t so conventional as to have More brazenly speak his mind from the outset. He is actually kind of cowardly in his plan to not say anything and skate away unnoticed. He’s not so much a rabble rouser as an overwhelmed man trying to stay out of the fray while not sacrificing his morality, which is a different take on a commonly told story. Scofield has a weary, but smart aleck, nature to him that at least keeps him interesting, even though the character is in fact kind of a dick (he’s often smug and belligerent to people who are trying to help him). The rivalry between More and Henry is interesting in that Henry is hardly in the movie at all, save for one notable, lengthy scene between the two. The conflict exists, but we’re not sure how much is Henry’s doing and how much are people moving about trying to please their unknowable master. I liked the characterization of Henry – he’s a boisterous, unstoppable force whose so used to getting his way that he laughs off any perceived flaw and is so feared as to have all his followers readily agree with him. It really shines a light on the danger of extreme power possessed by Henry.

King Henry VIII (Robert Shaw) and Thomas More (Paul Scofield). Despite being the central conflict of A Man For All Seasons, this is the only scene the two share.

The movie tends to have flaws in plotting. Several plot threads are never explained or resolved. At the beginning of the movie, More’s daughter is being courted by a young lawyer, but More’s refuses to give his OK to the marriage because the lawyer had denounced the Catholic Church for its rampant corruption. Sometime later, we learn they are married with no explanation for why More changed his mind. In another scene, we learn Henry is making everyone take an oath of loyalty (or disloyalty to the Catholic Church) and More explains to his daughter they could still feasibly take it and not violate their conscious, depending on what the wording of the oath is. In the next scene, More is in jail, since apparently there were no loopholes in the oath, although we never get to hear the damn thing to know what the objectionable language was or how More’s daughter escaped similar imprisonment.

There are two ways to view A Man For All Season’s Oscar win. On the one hand, it seems like a reaction to the changing youth culture and nascent counter culture by rewarding a traditional movie that favored old-time values and stoic virtue. Conversely, it is a movie that champions the rejection and repudiation of corrupt authority (albeit in favor of a second corrupt authority), which actually feeds into the emerging counter-culture. Could A Man For All Seasons have actually inspired the anti-war protest and hippie mantras of the coming years? Hardly likely, and yet A Man For All Seasons ends up a pale reflection of the tidal wave of anti-authority sentiment to come.

Other Oscars: Paul Scofield, Best Actor; Fred Zinnerman, Best Director; Best Adapted Screenplay; Best Costume Design; Best Cinematography;

Box Office:$28.35 Million (Fourth for the Year)

Other notable Films of 1966: Alfie*; The Russians Are Coming, the Russians Are Coming*; The Sand Pebbles*; Whose Afraid of Virginia Woolf?*; The Bible: In the Beginning$; The Good, the Bad and the Ugly; Grand Prix; Blowup; The Endless Summer; Georgy Girl; The Fortune Cookie; Batman;

*Best Picture Nominee

$Top Box Office ($34.9 Million)